L.S. Lowry: Capturing the Industrial Soul

The Enigma of the Matchstick Man

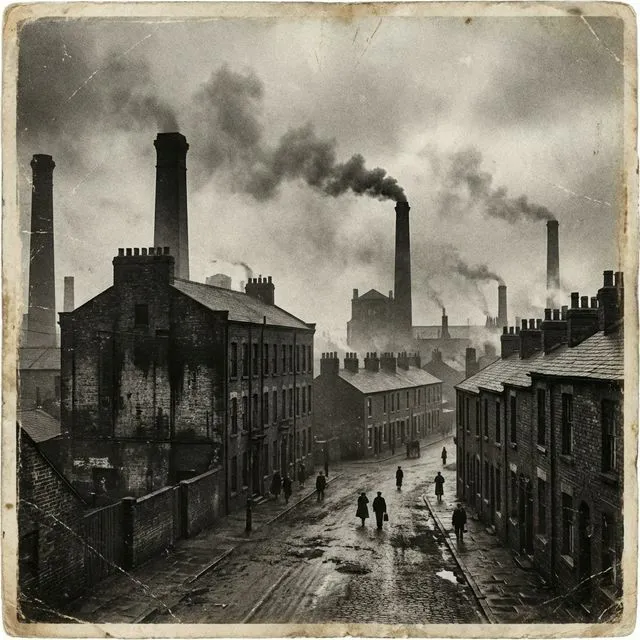

In the grand narrative of twentieth-century British art, Laurence Stephen Lowry (1887–1976) stands as a singular, often paradoxical figure. To the wider public, he is an affectionate icon, the man who immortalized the soot-choked skyline of the industrial North and populated it with his famous “matchstick men.” These figures became the visual shorthand for the working-class experience in mid-century England - a dialect of paint that spoke of clogs, shawls, and the factory whistle. Yet, within the corridors of the art establishment, Lowry has historically been viewed with a degree of skepticism, frequently categorized as a “Sunday painter,” a primitive talent, or a parochial eccentric whose artistic vision was limited to the mill gates of Lancashire.

This binary distinction - the beloved populist versus the critical outsider - obscures a far more intricate truth. The narrative that Lowry was an untrained “naïf” is a myth that has persisted for decades, yet it crumbles under the weight of archival evidence. Lowry was neither an amateur nor an accidental genius. He was a highly sophisticated draftsman, a product of the rigorous academic tradition, and a man who lived a strictly compartmentalized existence.

Recent investigations into the archives of the Manchester Municipal School of Art (now Manchester Metropolitan University) have fundamentally shifted our understanding of his work. Central to this reassessment is a specific document: the Student Registration Card for the 1914–1915 academic session. This administrative artifact serves as a key to decoding Lowry’s true artistic identity, proving that the man who painted the “industrial soul” of the North did so not through simple instinct, but through a synthesis of deep technical training and relentless observation.

The Evidence of the Academy: 1914–1915

The physical proof of Lowry’s dedication to formal art education is preserved within the Special Collections of Manchester Metropolitan University. The registration card from the autumn of 1914 places a twenty-six-year-old Lowry firmly in the classroom at a time when Europe was plunging into the First World War. For most professional artists, foundational studies are completed in their early twenties. The fact that Lowry was still registering for core modules at this age speaks to a persistence that borders on obsession.

By 1914, Lowry had already been attending evening classes since 1905. This document captures him in the tenth year of what would eventually be a twenty-year apprenticeship in the arts. He was not merely dabbling in recreational painting; he was engaged in a decade-long grind of academic study. Crucially, the card reveals that he was fully employed by the Pall Mall Property Company during this period. It documents the operational phase of his “double life”: a rent collector by day and a serious academic student by night.

Anatomy and the Logic of the “Stick Figure”

The specific courses listed on his registration card - “Anatomical Drawing” and “Life and Antique” - dismantle the criticism that Lowry’s “matchstick” style was born of an inability to draw realistic figures. “Anatomical Drawing” was a module that demanded a scientific understanding of the human form. The curriculum involved studying the skeletal structure and musculature, often drawing from articulated bones and écorché casts (models showing muscles without skin).

This rigorous training explains the peculiar weight and balance found in Lowry’s stylized figures. Even when reduced to their simplest forms, his figures possess a center of gravity that is anatomically sound. When a Lowry figure leans against a gale or hunches under a burden, the posture is dictated by the laws of physics and biology. The “matchstick” appearance is not a failure of draftsmanship; it is a modernist reduction. It represents the skeleton clothed in the absolute minimum visual data required to register as human. The 1914 card proves that Lowry spent his evenings studying the tibia and the pelvis, knowledge that allowed him later to execute his shorthand with intuitive precision.

Furthermore, his enrollment in “Life and Antique” confirms his long-term engagement with classical proportion and the nude figure. Drawing from casts of classical sculpture and living models, Lowry mastered the rules of Western art before he chose to break them. As he later remarked, years of drawing the figure were the only thing that truly mattered. His eventual style was a deliberate departure from this naturalism, a choice made by an artist who possessed the technical skills to paint traditionally but chose a different path to capture the industrial condition.

The Myth of the Untrained Eye

The romanticized notion of Lowry as a “naive” artist - a Northern equivalent to self-taught painters like Henri Rousseau - was a narrative Lowry himself occasionally encouraged to disarm critics. However, the historical timeline renders this impossible. His education spanned from 1905 to 1925, moving from the Manchester Municipal School of Art to the Salford School of Art. While his contemporaries might have spent a few years at the Slade in London, Lowry spent two decades in the night schools of the North.

This sheer volume of study suggests that his flattening of perspective and simplification of form were conscious stylistic evolutions. He learned the rules of perspective in order to dismantle them effectively, creating a “cultivated naivety.”

The French Impressionist Influence

A pivotal figure in Lowry’s development was Pierre Adolphe Valette, a French Impressionist who taught at the Manchester School of Art. Valette brought the avant-garde techniques of the continent to the industrial city. He painted Manchester not as a grim pit, but as a modern metropolis softened by atmosphere, using purples and greys to capture the fog and rain.

Valette taught Lowry to see the city as a worthy subject for art. Before this influence, the warehouses and mills were seen purely as utilitarian eyesores. Valette showed Lowry the atmospheric beauty inherent in the urban landscape. While Lowry eventually rejected Valette’s soft, Impressionist “purple haze” in favor of a harsher, grittier reality, the fundamental lesson remained: the city was a stage. Lowry took the stage Valette built but lit it with the stark glare of the industrial reality rather than the romantic softness of Impressionism.

The White Background Epiphany

If Valette taught Lowry how to see, it was Bernard Taylor, his tutor at the Salford School of Art, who taught him how to paint. In his early years, Lowry’s canvases were dark and sombre, influenced by traditional academic tonalism. Taylor criticized these works, arguing they were “too dark” and the figures were lost in the gloom.

In response, Lowry experimented with a pure white background. When he presented this new approach, Taylor’s validation was immediate. The white ground became Lowry’s trademark, a technical solution that allowed him to silhouette his dark figures with graphic clarity. This evolution was not an accident of a primitive painter but the result of a feedback loop between a student and his professor.

The Double Life: The Rent Collector of Brown Street

For forty-two years, spanning from 1910 to 1952, L.S. Lowry lived a dual existence. He worked as a rent collector and chief cashier for the Pall Mall Property Company, based at 36 Brown Street in Manchester. This profession was not a hindrance to his art; rather, it was the engine that drove it. It provided him with structured access to the urban environment and a unique psychological vantage point.

Lowry went to great lengths to conceal this part of his life, fearing the art world would dismiss him as a hobbyist. It was only after his death that the full extent of his career was revealed. However, this job was crucial because it forced him to walk specific routes through the most deprived districts of Manchester and Salford - places like Hulme, Ancoats, and Pendlebury - week after week, year after year.

The Psychogeography of the Slums

Lowry’s daily rounds were a form of “psychogeography.” Unlike a studio artist who might visit a location once to sketch, Lowry absorbed the mood and decay of the city through repetition. He knew every broken window, every peeling door, and the specific way smoke curled from the chimneys.

This professional access facilitated projects like his 1930 drawings of Ancoats, a notorious slum. His role as a rent collector gave him a legitimate reason to stand on street corners in these “pictorially unpromising” areas without drawing suspicion. The resulting drawings are devoid of sentimentality; they are descriptive and uninflected, mirroring the objective gaze of a clerk filling out a ledger.

The constraints of his job also dictated his artistic process. Unable to set up an easel in the middle of a collection round, Lowry developed the habit of sketching on whatever paper was available - backs of envelopes, rent books, and receipts. This necessity for speed contributed to his shorthand style, capturing the essence of a figure in seconds before taking the raw data back to his studio in Pendlebury.

The Outsider’s Gaze

The role of the rent collector is inherently isolating. To the tenants, Lowry was an authority figure, the man demanding money. This social dynamic permeates his canvas. The figures in his paintings rarely make eye contact with the viewer or each other; they are isolated units moving through the crowd. This reflects the gaze of the collector: observing the masses but remaining fundamentally separate from them. The existential loneliness Lowry often spoke of was mirrored in his professional life - a man who knocked on thousands of doors but remained on the threshold.

The Chemistry of the Industrial Soul

Lowry’s artistic style was a highly technical language designed to translate the specific atmospheric conditions of the North into paint. His celebrated “limited palette” was not a result of poverty but a disciplined aesthetic choice. He used only five colors: Flake White, Ivory Black, Vermilion, Prussian Blue, and Yellow Ochre.

The Science of Smog

The foundation of Lowry’s atmosphere was Flake White. Chemically known as basic lead carbonate, its composition can be represented as 2PbCO3·Pb(OH)2. This pigment is dense, opaque, and dries to a strong, flexible film. Lowry used it to build up the physical texture of the atmosphere, applying layer upon layer to create the “hazy white sky” that defines his landscapes.

In the industrial North, the sky was rarely blue; it was a diffuse, milky white caused by the scattering of light through coal smoke. By avoiding pure greens and relying on the chemical density of lead white, Lowry captured the pollution of the atmosphere, applying layer upon layer to create the “hazy white sky” that defines his landscapes.

In the industrial North, the sky was rarely blue; it was a diffuse, milky white caused by the scattering of light through coal smoke. By avoiding pure greens and relying on the chemical density of lead white, Lowry captured the pollution of the atmosphere with scientific accuracy. He rarely used medium to dilute his paint, preferring to use it straight from the tube to achieve a rugose, textured surface that mimicked the worn stone of the city.

The Symbolism of the Mass

The “matchstick men” were a deliberate stylization to solve the problem of depicting the “faceless masses.” In the industrial system, the individual is subsumed by the crowd and the factory. Lowry’s figures reflect this dehumanization. By stripping away facial features, he emphasized the collective identity of the workers, likening them to ants swarming around the mill.

He explicitly stated that natural figures would have “broken the spell” of his vision. The figures are symbols - glyphs representing human presence without the distraction of personality. This approach aligns him more with Modernist abstraction than naive folk art.

The Landscape: Mills as Cathedrals

Geography was destiny for Lowry. While often called a Manchester artist, his spiritual home was the industrial corridor of Salford. His move to Pendlebury in 1909, initially resented as a social comedown, became the catalyst for his art. It was at Pendlebury station in 1916 that he experienced a moment of rapture, seeing the mill “turning out” against the sky. He realized then that the industrial scene had never been properly painted.

In Lowry’s secular landscapes, the cotton mill replaces the cathedral. In works like The Mill, Pendlebury (1941), the architecture is monumental, dwarfing the figures and emphasizing the dominance of industry over humanity. He treated the chimneys and factories with the same reverence Canaletto applied to Venetian palaces.

There is a distinct difference between his depictions of Manchester and Salford. Manchester represented the commercial hub and the site of his office; Salford was the industrial heartland, the home of the matchstick men. His paintings of Salford often feature open spaces like Peel Park, where the industrial crowd is at leisure, yet still under the inescapable shadow of the smoking chimneys.

Conclusion: The Trained Visionary

The Student Registration Card of 1914 is a small document with profound implications. It shatters the myth of L.S. Lowry as an untrained eccentric and reveals him as a dedicated academician. His genius lay in his ability to synthesize two opposing worlds: the classical training of the art school and the gritty, repetitive reality of the rent collector.

Lowry used the tools of the academy - anatomy, composition, and tonal control - to document the “industrial soul” of a world he knew intimately through his ledger books. He was a spy in the house of industry, a man who walked the streets disguised as a clerk, gathering visual data to transmute into the definitive imagery of the 20th-century North. He did not just paint the smoke; he painted the society that lived beneath it, capturing the mood and rhythm of an era with a vision that was anything but simple.

References & Further Reading

- L.S. Lowry: The Art and the Artist

- Visions of Matchstick Men and Icons of Industrialization

- Lowry and the Local: British Art Studies

- The Haunting of L.S. Lowry: Class, Mass Spectatorship and the Image