The Hydraulic Revolution: How Engineering Defeated Cholera in the Victorian North

The Hydraulic Revolution: How Engineering Defeated Cholera in the Victorian North

Executive Summary The cholera epidemic of 1866, historically designated as the “Fourth Visitation,” constitutes a pivotal moment in the infrastructural history of Northern England. While the foundational etiology of the disease had been hypothesized by John Snow in London a decade prior, it was the industrial metropolises of the North - specifically Leeds, Newcastle upon Tyne, and Liverpool - that transformed these theoretical frameworks into tangible governance and massive engineering projects. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the 1866 outbreak within the northern industrial corridor, arguing that the true victory lay not in the drawing of maps, but in the Hydraulic Revolution that followed.

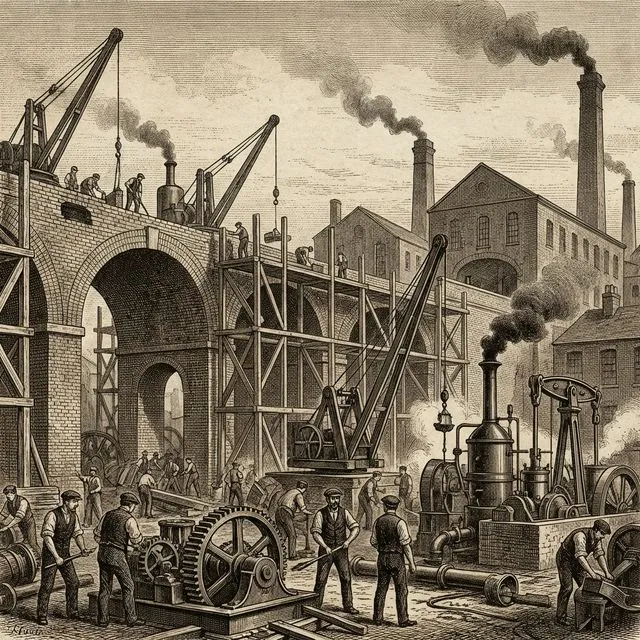

The analysis delineates the catastrophic sanitary baseline of the 1860s, characterized by the “midden” systems of Leeds and the tenement density of Newcastle. It traces the epistemological rupture that occurred as the evidence of death clusters forced a transition from the miasmatic theory of atmospheric corruption to the germ theory of water-borne transmission. Furthermore, it details the resulting construction boom, driven by the technocratic vision of figures such as Edward Filliter and Dr. W.S. Trench. This culminated in the construction of monumental waterworks like the Washburn Valley scheme and the rigorous enforcement of the Sanitary Act of 1866. The report argues that while data visualization provided the diagnosis, it was the “moral certainty” of engineering - concrete, steel, and brick - that dismantled the laissez-faire urbanism of the early Victorian era.

1. The Engineering of Survival: From Diagnosis to Construction

The visualization of disease in the nineteenth century was not a static artistic endeavor but the precursor to a massive physical intervention. By 1866, the “Mortality Map” had served its purpose as a diagnostic tool, revealing the invisible geography of contagion to the municipal authorities of Northern England. However, the true story of 1866 is how these diagnoses were converted into an administrative weapon: infrastructure. Unlike the broad strokes of earlier decades, the response in 1866 was defined by a granular focus on street-level drainage, hydraulic connectivity, and the physical restructuring of the urban environment.

1.1 The Leeds Prototype: Identifying the Infrastructural Failure

To understand the engineering operations of 1866, one must examine their lineage in the West Riding of Yorkshire. While John Snow is frequently cited as the pioneer of disease tracking, the industrial town of Leeds possesses a distinct tradition initiated by the surgeon Robert Baker. Baker’s seminal work, produced in the wake of the 1832 epidemic and formalized in his 1842 report, established the logic that would dominate Northern public health: that biology is a function of geology and plumbing.

Baker’s innovation lay in his refusal to view the town as a homogeneous unit. His early investigations utilized a plan of Leeds to identify the precise locales of cholera cases, creating a stark argument that disease was not an indiscriminate scourge of divine providence, but a calculated consequence of environmental neglect. He demonstrated that the “track of the Cholera is nearly identical with the track of the fever,” and that both were inextricably bound to the “uncleansed and close streets” of the eastern wards, such as the Bank and the Leylands.

By 1866, this prototype had evolved into a sophisticated bureaucratic standard. The “epidemic consciousness” within the Leeds Corporation meant that authorities no longer just watched dots on a map; they monitored the flow of water. The memory of the 1849 epidemic, which had claimed 2,323 lives in Leeds (a rate of 125 per 10,000), ensured that the spatial monitoring of the 1866 outbreak was rigorous. Authorities knew where the infrastructure would fail before the first case was registered, allowing for a targeted sanitary response that prevented the 1866 outbreak from reaching the catastrophic mortality levels of its predecessors.

1.2 Liverpool: Demolition as Sanitation

In Liverpool, the response in 1866 reached its most aggressive administrative form under the stewardship of Dr. William Stewart Trench, the Medical Officer of Health. Liverpool, frequently stigmatized as the “unhealthiest town in England” due to its status as a global port and the density of its cellar population, utilized data as a direct extension of the Liverpool Sanitary Amendment Act of 1864.

The Borough of Liverpool’s response was a triumph of forensic precision. Unlike general density studies, Trench’s analysis targeted specific administrative subdivisions, such as the Scotland Ward, cross-referencing mortality data against the known locations of “fever nests” and insane property.

- The Geometry of Enforcement: The city employed a dot-density technique to signify mortality clusters, which were then cross-referenced with the layout of “courts” (narrow, dead-end communal yards) and cellar dwellings. This synthesis revealed that while the absolute number of deaths in 1866 was lower than in 1849, the disease remained stubbornly endemic in areas of high indigence.

- Strategic Demolition: The data served as the evidentiary basis for the “presentment” of buildings for demolition. Under the 1864 Act, the Corporation required “moral certainty” that a specific property was injurious to health before it could violate private property rights and order its destruction. The analysis provided this certainty. When Trench presented his findings to the Grand Jury, the clustering of death around specific “courts” acted as an unassailable indictment of the landlord’s neglect, facilitating the physical clearance of the worst slums in the borough.

1.3 Newcastle upon Tyne: The Infrastructure of Neglect

In Newcastle, the crisis of the 1866 epidemic was viewed through the lens of a composite “infrastructure audit” that linked mortality to the failures of the private water monopoly. Following the devastation of the 1853 epidemic, which had killed over 1,500 residents, the town’s sanitary surveillance had been heightened.

The response in Newcastle was a collaborative exercise between the medical establishment, represented by Dr. Embleton of the Newcastle Fever Hospital, and the engineering department led by the Town Surveyor, Thomas Bryson. Bryson had begun surveying the town’s sewerage system in the mid-1850s, a task that involved creating detailed plans denoting the presence - or often the absence - of drainage.

- The Intersection of Data: In 1866, these drainage plans were overlaid with the mortality returns provided by Dr. Embleton. Embleton’s reports offered a textual analysis of the “confined and unwholesome yards” where typhus and cholera co-mingled, creating a grid of accountability.

- The Water Layer: Crucially, the investigation of 1866 in Newcastle also tracked the distribution network of the Whittle Dean Water Company. By correlating the areas of highest mortality with the specific supply lines of the company, the authorities could demonstrably link the water source to the disease, a technique that mirrored John Snow’s work but was applied on a municipal scale to force corporate restructuring.

2. The Crisis: The Sanitary Landscape of the 1860s

The operational utility of these investigations can only be understood against the backdrop of the profound sanitary crisis that engulfed the industrial North in the 1860s. Despite the legislative advances of the 1840s, the physical reality of towns like Leeds and Newcastle remained perilous. The rapid demographic expansion driven by the textile, coal, and shipping industries had vastly outpaced the development of municipal infrastructure, creating an urban ecology ideally suited for the propagation of water-borne pathogens.

2.1 Leeds: The Midden System and the River Aire

Leeds in the 1860s was structurally defined by the “midden” system. In the absence of a comprehensive water-carriage sewer system, human waste was collected in open cesspools or ash-pits located in the courtyards of working-class housing. These middens were often unlined, allowing liquid filth to seep into the surrounding soil and contaminate the shallow wells that many residents still relied upon.

The river system, theoretically the town’s lifeline, had become its greatest threat. The River Aire, which bisected the town, was described as a “Ganges of the North” not for its sacredness, but for its burden of filth.

- The Water Paradox: While Leeds boasted a piped water supply dating back to the 17th-century works of George Sorocold, by 1866 the system was critically compromised. The primary supply was derived from the River Wharfe at Arthington. However, as the Borough Surveyor Edward Filliter reported, this source had become heavily polluted by the “large and constantly increasing quantities of filth” discharged by paper mills, tanneries, and woolen mills upstream of the intake.

- The Consumption Crisis: The crisis was also one of quantity. Filliter noted that the average consumption had reached 4.5 million gallons per day, dangerously close to the parliamentary limit of 6 million gallons. In the event of a drought or increased demand, the pressure in the mains would drop, causing a suction effect that could draw groundwater - contaminated by the middens - back into the supply pipes.

2.2 Newcastle upon Tyne: The Tenement Disaster and the Water Monopoly

The sanitary crisis in Newcastle was distinguished by the peculiar density of its housing stock and the malfeasance of its private water supplier. The working class population was concentrated in “chares” - narrow, medieval alleys leading down to the Quayside - and in subdivided tenements that lacked basic ventilation or sanitation.

| Feature | Leeds | Newcastle upon Tyne | Liverpool |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Housing Type | Back-to-Back Terraces | Chares / Subdivided Tenements | Cellar Dwellings / Courts |

| Primary Sanitation | Midden / Ash-pit | Communal Privy | Midden / Cesspool |

| Water Supply Model | Municipal / Mixed Private | Private Monopoly (Whittle Dean) | Municipal (Corporation) |

| Key Disease Vector | River Pollution (Wharfe) | Contaminated River Intake (Tyne) | Port Entry / Overcrowding |

| Mortality Driver | Drainage failure | Housing density & Water quality | Immigration & Density |

- The Whittle Dean Scandal: The primary driver of the crisis in Newcastle was the failure of the Whittle Dean Water Company. During the 1853 epidemic, the company had been exposed for supplementing its supply with water pumped directly from the River Tyne at Elswick - a location downstream from the town’s own sewer outfalls. Although the company had ostensibly improved its infrastructure by 1866, obtaining an Act to draw water from the River Pont, public trust was non-existent. The recurrence of cholera in 1866 was immediately interpreted by the populace and the press as evidence that the company was once again pumping “choleraic sewage” into the mains.

2.3 Liverpool: The Gateway of Contagion

Liverpool presented a unique sanitary challenge as the “gateway of empire.” The constant flux of sailors, immigrants, and transmigrants created a hyper-mobile population that was difficult to surveil.

- The Cellar Problem: Despite the aggressive provisions of the 1846 Sanatory Act, thousands of Liverpool’s poorest residents still lived in cellar dwellings - subterranean rooms often flooded with sewage from the overflowing court drains above. Dr. Trench’s 1866 reports highlighted that while the Corporation had closed many of the worst cellars, the sheer pressure of population growth, fueled by Irish immigration, forced families back into these condemned spaces.

- The Port Factor: The expansion of the steamship trade meant that vessels were larger and arrived more frequently, increasing the probability of cholera being imported from continental Europe or the Mediterranean. The challenge in Liverpool was thus as much about the docks as it was about the town itself.

3. The Science of Flow: Defeating the Miasma

The 1866 epidemic represents a watershed moment in the history of public health not because of its scale - it was significantly less lethal than the outbreak of 1849 - but because it marked the definitive epistemological triumph of the water-borne theory over the miasma theory. The investigations of the North provided the empirical battleground where this shift was contested and ultimately validated.

3.1 The Decline of Miasma and the Rise of “Superadded Agency”

For the first half of the nineteenth century, the medical establishment in Northern England had adhered to the miasma theory, which posited that cholera was caused by “bad air” arising from rotting organic matter. This theory dictated the early sanitary responses: limewashing walls, street sweeping, and the removal of “nuisances.” However, the persistence of cholera despite these measures created a crisis of confidence.

By 1866, the intellectual landscape had been reshaped by the statistical rigor of William Farr at the Registrar General’s Office and the epidemiological investigations of J. Netten Radcliffe. Although John Snow had published his findings on the Broad Street pump in 1854, it was Radcliffe’s investigation of the 1866 East London outbreak that provided the irrefutable “London proof” required to sway the Northern authorities.

- The Mechanism of Proof: Radcliffe and Farr demonstrated that the explosion of cholera in East London was strictly confined to the area supplied by the Old Ford reservoir of the East London Water Company. This was not a matter of “bad air,” which would have drifted across parish boundaries, but of “superadded agency” - a specific poison distributed through a specific pipe network.

- Northern Application: This logic was immediately applied in the North. In Newcastle, the Medical Officer and the Town Surveyor ceased looking for “smells” and started looking for “valves.” The focus shifted from the atmosphere to the hydraulic infrastructure.

3.2 The Newcastle Natural Experiment

The most dramatic validation of the water-borne theory in the North occurred in Newcastle during September 1866. The timeline of the outbreak provided a natural experiment that mirrored Snow’s Broad Street pump intervention, but on a city-wide scale.

Table 2: The Newcastle Mortality Timeline (September-October 1866)

| Date | Event / Data Point | Causality Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-Sept 15 | Whittle Dean Co. pumping Tyne water at Elswick. | Exposure Phase: Contaminated water enters the mains. |

| Sept 15 | Order given to stop pumping from the Tyne. | Intervention: The vector is severed. |

| Sept 17 | Deaths peak at 102 in a single day. | Lag Phase: Incubation period of previously infected. |

| Sept 23-25 | Daily deaths drop to range of 63-81. | Decline: Cessation of new primary infections. |

| Sept 29 | Daily deaths drop to 23. | Collapse: The epidemic curve breaks. |

| Oct 27 | Zero deaths recorded. | Resolution: Validation of water-borne theory. |

As detailed in the records, the rapid subsidence of the epidemic exactly 15 days after the supply of “choleraic sewage” was cut off provided undeniable proof. The mortality data, which had shown clusters of death in the areas supplied by the Elswick station, suddenly flattened. This direct cause-and-effect relationship destroyed the credibility of the miasma theory in Newcastle and empowered the Corporation to demand total control over the water supply.

3.3 The Role of Statistical Visualization

The shift was also driven by the work of William Farr, who used the data from 1866 to produce statistical visualizations that correlated mortality with elevation and water source. Farr’s reports, which influenced Northern reformers like Trench and Filliter, showed that mortality was not a random variable but a function of infrastructure. The data became a statistical table, and the table became a mandate for engineering.

4. The Hydraulic Revolution: Infrastructure as Cure

The ultimate legacy of the 1866 cholera epidemic was the physical reconstruction of the Northern industrial city. The “moral certainty” provided by the investigations and the “London proof” of water-borne transmission galvanized municipal corporations to abandon the penny-pinching localism of the 1850s and embark on a period of massive capital investment in hydraulic infrastructure.

4.1 Leeds: The Washburn Valley Scheme

In Leeds, the immediate consequence of the 1866 scare was the authorization of the Washburn Valley Waterworks Scheme, a project of pharaonic ambition designed to secure the town’s health for the next century.

- The Filliter Report (1866): In September 1866, amidst the heightened “epidemic consciousness,” Borough Surveyor Edward Filliter presented his decisive report. He evaluated four potential sources: the River Ure, the River Nidd, the Burn/Laver, and the River Washburn. Filliter recommended the Washburn scheme for its combination of “economy and quality,” noting its water was “soft and pure” and the rainfall in the catchment area was abundant.

- The Engineering Solution: The scheme involved the construction of a chain of four reservoirs: Lindley Wood (compensation), Swinsty (service), Fewston (storage), and Thruscross (storage). This network would gravity-feed water to the Eccup reservoir, bypassing the polluted River Wharfe entirely.

- Political Conflict: The project was not without opposition. It was initially estimated at £150,000 but the costs ballooned to £410,000 under the consultancy of Thomas Hawksley. Local landowners, led by F.H. Fawkes, fought the bill in Parliament, and some council members argued for a yet more ambitious scheme to tap the Lake District. However, the shadow of the 1866 data ensured the Corporation’s resolve; the risk of another epidemic was deemed more costly than the reservoirs.

4.2 Newcastle: Taming the Tyne and the 1866 Act

In Newcastle, the result was the permanent alienation of the water supply from the urban river. The Whittle Dean Water Company, forced to rebrand and restructure as the Newcastle and Gateshead Water Company, was compelled by the Sanitary Act of 1866 to abandon the Tyne intake at Elswick forever.

- The Sanitary Act of 1866: This piece of national legislation, passed in the heat of the epidemic, transformed the regulatory landscape. It changed the powers of local Boards of Health from “permissive” to “compulsory.” It defined overcrowding as a legal nuisance and gave authorities the power to inspect the interior of private dwellings - a direct lesson from the conditions in the Newcastle tenements.

- Sewerage Expansion: The infrastructure plans of Thomas Bryson began to translate into reality. The red lines on paper became brick sewers underground. The 1866 crisis empowered the Town Council to enforce the connection of private drains to the main sewers, slowly eliminating the “midden” culture that had plagued the town.

4.3 Liverpool: Port Health and Slum Clearance

In Liverpool, the 1866 experience solidified the city’s strategy of “sanitary interventionism.” The Mortality data’s evidence of clustering in the “courts” justified the continued aggressive application of the 1864 Sanitary Amendment Act. By the late 1860s, Liverpool was demolishing unsanitary housing at a rate unmatched by any other British city. Furthermore, recognizing the “port disease” nature of cholera, Liverpool established a rigorous Port Health Authority system, utilizing quarantine and medical inspection to intercept the disease before it could disembark - a direct lesson from the analysis of 1866.

4.4 The Long-Term Epidemiological Transition

The infrastructure improvements initiated in 1866 had a profound and lasting effect on the mortality regimes of Northern towns. As indicated by long-term data, diarrhoeal mortality began a decisive decline following these interventions. While 1866 was the last major cholera epidemic to strike England, the reservoirs and sewers built in its wake also eradicated typhoid and dysentery as major killers by the turn of the century. The public health focus of the late Victorian era gradually shifted from tracking sudden, catastrophic death to monitoring the slower, chronic attrition of tuberculosis and infant mortality - a testament to the victory of the sanitary engineers over the water-borne scourges of the mid-century.

5. Conclusion

The 1866 cholera epidemic in Northern England serves as a defining case study in the power of engineering to drive social and physical survival. It was the moment when the “Mortality Map” evolved from a passive record of tragedy into a justification for massive construction. By scientifically proving the correlation between filth, water, and death, reformers in Leeds, Newcastle, and Liverpool were able to dismantle the paralysis of the miasma theory and replace it with the hydraulic certainty of the germ theory.

The legacy of this revolution is written in the stone embankments of the Washburn Valley reservoirs and the vast intercepting sewers that run beneath the streets of Tyneside. These massive capital projects were not merely engineering feats; they were the physical manifestations of a new political consensus - forged in the crisis of 1866 - that public health was a purchasable commodity, secured through the rigorous application of data, law, and concrete. The investigation of 1866 did not just visualize the Victorian health crisis; it laid the foundation for the modern sanitary city.

Sources

- HIDDEN BENEATH OUR FEET: The Story of Sewerage in Leeds, Sellers, 1997.

- LEEDS CORPORATION, 1835 - 1905: A History of its Environmental, Social and Administrative Services.

- Famine Disease and The Irish: Historical Analysis of Migration and Health.

- City of the Plague: Victorian Liverpool’s Response to Epidemic, Liverpool University Press.

- Report on the cholera epidemic of 1866 in England: Supplement to the twenty-ninth annual report of the registrar-general.

- A Comparative Study of the Origins and Development of Municipal Housing in Liverpool and Newcastle, c.1835-1914.

- Cholera as a ‘sanitary test’ of British cities, 1831–1866: PubMed Central.

- Waterworks, municipal government and the environment in twentieth-century Britain: Urban History, Cambridge University Press.