The Bank of England’s Northern Branch: Architecture of Power

Introduction: The Stone and the Sovereign

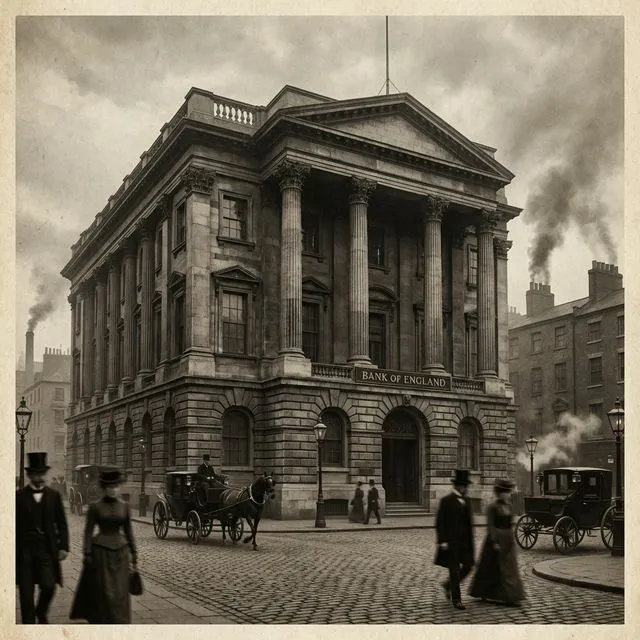

In the early decades of the 19th century, Newcastle upon Tyne presented a striking paradox to the observer. It was a city of profound duality, defined by a violent collision between the gritty reality of production and the high ideals of civilization. On one side lay the roaring engine of the British Industrial Revolution: a landscape scarred by the relentless extraction of coal, the forging of iron, and a rapidly expanding proletariat workforce living beneath the shadow of smoke-belching chimneys. On the other side, however, a different city was rising - one of the most ambitious and refined urban planning projects in European history. This was the birth of Grainger Town.

At the intersection of these two contrasting worlds stood a singular edifice: the Bank of England’s branch at 33–41 Grey Street. Constructed between 1835 and 1838, this building was far more than a mere administrative outpost for financial transactions. It was a calculated fortification. Following the financial traumas of the preceding decade, the central bank required a physical manifestation of order, stability, and imperial authority to impose upon the volatile industrial frontier of the North.

This article delves into the history of this architectural landmark, exploring how it functioned simultaneously as a temple of commerce and a military stronghold. By examining the forensic details of its design, the controversy of its architects, and the “subterranean reality” of its vaults, we reveal how the visual language of classical antiquity was mobilized to secure the empire’s gold against the threats of fire, riot, and economic collapse.

The Economic Imperative: Securing the North

To understand the architecture of the Grey Street branch, one must first understand the desperation that necessitated its construction. The Bank of England did not expand into the provinces for the sake of aesthetics; it did so as a survival strategy for the national economy.

The Trauma of 1825

The catalyst was the catastrophic Financial Panic of 1825. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, a speculative bubble burst, shattering the liquidity of the British banking system. At that time, the Bank of England was the sole joint-stock bank permitted by law, but its stabilizing influence was largely confined to London. The rest of the nation relied on a fragile network of small, private “country bankers” who issued their own notes. When the panic struck, these undercapitalized institutions fell like dominoes; seventy-three of them suspended payments in a single year, wiping out savings and paralyzing trade.

In response, the government passed the Country Bankers Act of 1826. This pivotal legislation shattered the old monopoly, allowing joint-stock banks to form outside a 65-mile radius of London and empowering the Bank of England to establish provincial branches. The mission was clear: circulate stable, central bank notes to replace the worthless paper of broken private banks.

The “Dead Cats” of Clavering Place

The Bank’s arrival in Newcastle was initially far from glorious. Opening on April 21, 1828, the first branch was located in temporary premises at Clavering Place. This location proved to be a disaster that highlighted the need for a purpose-built fortress. The site was peripheral and insecure, subject to the indignities of a rough industrial town. Historical correspondence reveals that the Bank Agent was forced to hire an elderly woman to chase away “troublesome” children, while refuse and even dead cats were frequently thrown over the garden walls.

Worse than the physical insults was the operational hostility. The local business community, fiercely protective of their regional autonomy, viewed the “Bank of London” as a predator. Local private banks engaged in what was described as “guerrilla warfare,” purposefully hoarding Bank of England notes and sending the poor to the branch to demand gold coins in exchange, attempting to drain the branch’s reserves and incite a run. Furthermore, the Clavering Place building was damp, causing the stock of bank notes to rot in the vaults. By 1836, the Directors in London realized that to command respect and ensure security, they needed to move from the periphery to the center. They needed a stronghold.

The Architecture of Security

The move to Grey Street in 1838 was a strategic masterstroke. It placed the Bank in the beating heart of Richard Grainger’s “City of Palaces,” physically distancing it from the squalor of its previous home. The new building was designed to be a document of profound duality: a public face of serene Grecian rationality masking a core of hardened security.

A Semiotic Analysis of the Façade

The exterior of the building is a masterclass in the “semiotics of stability.” Constructed from high-quality sandstone ashlar, it rejected the stucco finishes popular in London for a material that implied geological permanence. The design organizes the structure into a clear hierarchy of strength, using classical orders to communicate the bank’s function to both the literate and illiterate public.

The Foundation: The ground floor features channelled rustication - deeply grooved stone blocks that visually anchor the building to the earth. in the language of classical architecture, rustication signifies the primitive, the foundational, and the impenetrable. For a bank operating in a volatile city, this was a deliberate signal that the institution was immune to market shifts. The blueprint specified six-panelled double doors set into this layer, reinforced by heavy glazing bars, creating a defensive perimeter against the physical threats of the street, including the potential for mob violence during the Chartist era.

The Authority: Rising above this fortified base is a Giant Corinthian Order spanning the second and third storeys. Unlike the simpler Doric orders found elsewhere, the Corinthian order - with its ornate acanthus leaf capitals - was historically associated with the most significant civic temples of antiquity. By wrapping the bank in this specific order, the architects elevated money-lending to the status of a civic religion. The vertical pilasters unified the upper floors, making the building appear larger and more imposing than its neighbors, asserting a visual dominance over the street.

The Hidden Fortress: Vaults and Fireproofing

While the façade projected openness, the interior was governed by paranoia. The internal layout was heavily influenced by C.R. Cockerell (1788–1863), the architect to the Bank of England who succeeded Sir John Soane. Cockerell was obsessed with the physical security of provincial branches.

The “stronghold” nature of the Newcastle branch was concentrated in its subterranean levels. The strongrooms were constructed with double-walled masonry, often featuring an air gap or sand filling to prevent physical breaching and provide insulation against fire. Crucially, the design distinguished between two types of assets:

- The Bullion Vault: Lined with iron plates, this “safe within a safe” held the gold sovereigns required to back the paper currency and pay the wages of the northern coalfields.

- The Book Room: Designed with the same fireproof rigour as the gold vault, this room held the ledgers. In an era before digital backups, the destruction of the “Books” meant the erasure of the bank’s legal memory.

Furthermore, the building was designed as a continuously inhabited fortress. The upper floors contained domestic quarters for the Bank Agent. The presence of the manager living “above the shop” - accessed by separate 8-panelled house doors - ensured 24-hour onsite surveillance.

The Authorship Debate: Dobson vs. Wardle

The building stands within Grainger Town, a development dominated by the figure of John Dobson, often cited as the “most noted architect in northern England.” Dobson’s stylistic fingerprint, a clean and masculine neoclassicism, defines the city. However, the specific authorship of the Bank of England building remains a subject of historical nuance.

While John Dobson is credited with the overarching design of the east side of Grey Street, heritage listing records explicitly attribute the Bank of England building to John Wardle. Wardle was an architect employed directly within Richard Grainger’s office. This distinction highlights the nature of the “Grainger Town” phenomenon: it was a highly commercial operation. Grainger often utilized in-house architects like Wardle to execute designs that adhered to the master plan established by Dobson.

Therefore, the building represents a convergence of Dobson’s theoretical vision and Wardle’s pragmatic execution. Dobson’s influence is visible in the strict adherence to classical proportions and the urban scale, while Wardle’s hand was likely responsible for the specific detailing of the banking hall and the integration of the building into the mixed-use terrace. This collaboration, however, was not destined to last. The relationship between Dobson and Grainger eventually collapsed in acrimony over unpaid fees for a staircase and a painted ceiling, a rupture that highlights the tension between artistic idealism and the ruthless financial speculation that built the city.

Atmosphere: The Sublime Contrast of Smoke and Stone

To fully appreciate the impact of the Bank of England branch in the 19th century, one must look beyond the clean lines of architectural drawings and imagine the atmospheric reality of the era. Newcastle was the capital of the Great Northern Coalfield, and the “pall of industrial smoke” was a pervasive element of daily life.

The visual record of Grainger Town is often viewed through the idealized lens of J.W. Carmichael, a landscape artist whose paintings served as propaganda for the new development. His 1831 work, Proposed new street for Newcastle, depicts a gleaning, sun-drenched utopia populated by elegant citizens. However, even Carmichael included details like a farmer leading a horse, hinting at the tension between the market town and the metropolis.

The reality was far grittier. The local sandstone, though honey-colored when quarried, was highly reactive to the industrial atmosphere. The smoke from the surrounding industries contained high levels of Carbon (C) and Sulfur (S), specifically sulfur dioxide. This resulted in a chemical process known as “time-staining.”

The pristine classical columns of the Bank rapidly absorbed the soot, turning into striking, velvet-black monoliths. This transformation created a visual effect that contemporary observers often found “Sublime.” The contrast between the refined Corinthian capitals - symbols of high culture and order - and their blackened, soot-stained surfaces - evidence of industrial might - embodied the dual nature of British power. It was wealth created by fire and smoke, dressed in the robes of Rome.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Stone

The Bank of England’s Northern Branch was more than a building; it was a mechanism of stabilization inserted into a chaotic landscape. Its rusticated base and iron-lined vaults were technologies of trust, designed to provide psychological assurance to a nervous public.

By anchoring itself in the heart of Grainger Town, the Bank contributed to one of the most successful urban interventions in history. It helped transform Newcastle from a medieval town of brick and timber into a “City of Palaces” that dared to challenge the architectural supremacy of London. While the gold sovereigns are long gone, and the building has ceased to function as a branch of the central bank, it remains a silent witness to the ambition of the 19th century. It stands as a testament to a time when architecture was mobilized to impose civility upon the industrial frontier, creating a fortress that held the wealth of the North safe within the Tyneside soil.

References & Further Reading

- The Architecture of Finance in Newcastle: A Fortress of Civility in the Industrial North

- C. R. Cockerell’s ‘Architectural Progress of the Bank of England’

- Richard Grainger’s vision for Grey Street, Newcastle

- The Streets of Newcastle – Grey Street

- The Bank of England Branch Banks, 1826-1831