The Rochdale Pioneers: Architects of the Co-operative Commonwealth

The Rochdale Pioneers: Architects of the Co-operative Commonwealth

The history of the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers is frequently reduced to a sentimental narrative: a tableau of twenty-eight impoverished weavers opening a meagre grocery store on a rainy night in Lancashire. While this image provides the movement with its emotional resonance, the true historical significance of the Rochdale Pioneers lies not in their retail operations, but in their constitutional innovation. The “Book of Rules,” formally registered as the “Laws and Objects of the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers” in 1844, represents one of the most sophisticated attempts in the nineteenth century to codify a new economic morality. This document did not merely outline the bylaws of a shop; it provided a comprehensive blueprint for the transition from competitive capitalism to a cooperative commonwealth.

The Geography of Despair: Rochdale in the “Hungry Forties”

To comprehend the radical nature of the 1844 Laws, one must first situate them within the visceral reality of the early Victorian era. The Pioneers were not operating in a vacuum; they were products of the “Hungry Forties,” a decade defined by economic depression and social turbulence.

Rochdale, a grim mill town in Lancashire, was dominated by the textile industry, specifically flannel weaving. By 1844, this industry was undergoing a painful, structural transition from handloom to power loom weaving. This mechanisation had catastrophic consequences for the local workforce. A weaver who might have commanded a respectable wage of 20 to 30 shillings a week in 1800 was often reduced to a starvation wage of 4 to 6 shillings by the 1840s.

Compounding this misery were the Corn Laws, which kept bread prices artificially high to protect domestic agriculture, and the general economic depression that followed the Plug Plot riots of 1842. The working class lived in squalid conditions, often dependent on the notorious “truck system,” where employers paid wages in goods or tokens valid only at company-owned stores. Alternatively, workers were trapped by debt to unscrupulous private shopkeepers who sold adulterated goods. In this environment, the creation of the Society was not a hobby; it was a desperate survival strategy against a hostile economic order.

The Intellectual and Legal Antecedents

The “Law and Objects” document is a synthesis of three distinct streams of thought: Owenite Socialism, Chartism, and the practical necessity of the Friendly Society movement.

Robert Owen, the Welsh philanthropist and social reformer, had long advocated for “Villages of Cooperation” where labour would be the standard of value. Many of the original Rochdale Pioneers, including key figures like Charles Howarth and James Smithies, were ardent Owenites. However, the Owenite movement had historically suffered from a fatal flaw: it relied heavily on philanthropic capital and top-down governance. Earlier cooperative attempts, such as those in Brighton led by Dr. William King or the first Rochdale attempt in the 1830s, had collapsed due to reckless credit extension and a lack of legal protection for community funds.

The legal environment of 1844 remained hostile to working-class economic organisation. Joint-stock companies were largely the preserve of the wealthy, and the legal framework for “societies” was restrictive. Here, the Pioneers executed a strategic masterstroke. They utilised the Friendly Societies Acts of 1836 and 1846 to register their rules.

By registering as a Friendly Society, the Pioneers gained “legal personality.” This meant the Society could hold property in the names of trustees, sue and be sued, and, crucially, protect the savings of its members from fraud or embezzlement by officers. This legal protection was paramount in convincing a skeptical working class to trust the new Society with their meagre capital. The local population was already scarred by financial betrayal, having seen the official Rochdale Savings Bank collapse in 1849 with disastrous losses to small savers.

“Law First”: The Hierarchy of Ambition

The foundational text of the Society is enshrined in “Law First” (often cited as Object 1 in the 1844 Rules). A close textual analysis of this section reveals that the “store” was never intended as the terminal goal of the Society. Instead, “Law First” outlines a phased, evolutionary strategy for total social reconstruction. The objectives were listed in a specific order of progression, moving from the immediate to the utopian:

- Capital Accumulation: “The establishment of a store for the sale of provisions and clothing, &c.” The store was merely the “engine” to generate initial capital through retail surplus and address the immediate need for unadulterated food.

- Housing Security: “The building, purchasing or erecting of a number of houses, in which those members desiring to assist each other in improving their domestic and social condition may reside.” This aimed to move beyond consumption to asset ownership, freeing members from the tyranny of slum landlords.

- Labor Control: “To commence the manufacture of such articles as the Society may determine upon, for the employment of such members as may be without employment, or who may be suffering in consequence of repeated reductions in their wages.” This was a direct response to the “double squeeze” of the 1840s (low wages and unemployment), aiming to make the Co-op the employer of last resort.

- Agricultural Autonomy: “The Society shall purchase or rent an estate or estates of land, which shall be cultivated by the members who may be out of employment, or whose labour may be badly remunerated.” This sought to reconnect the displaced industrial worker with the land, ensuring food security independent of market fluctuations.

- The Utopian Goal: “That as soon as practicable, this society shall proceed to arrange the powers of production, distribution, education, and government, or in other words to establish a self-supporting home-colony of united interests.” The ultimate objective was the creation of a “state within a state.”

- Moral Reform: “That for the promotion of sobriety, a temperance hotel be opened in one of the Society’s houses as soon as convenient.”

This document demonstrates that the Rochdale Pioneers were not merely grocers; they were “community builders” who viewed the grocery trade as the most accessible lever to overturn the capitalist order.

The Governance Mechanism: The “Seven Principles”

While “Law First” defined the ends, the subsequent rules defined the means. These operational bylaws were drafted largely by Charles Howarth, a warper in a cotton mill and a determined socialist. Although the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) would not formally codify the “Rochdale Principles” until 1937, the 1844 document established the operational DNA of the movement.

Democratic Control (One Member, One Vote)

The 1844 rules established a governance structure that was radically democratic for its time. Unlike joint-stock companies where voting power was proportional to shares held, the Rochdale rules insisted on “one member, one vote” regardless of the amount of capital invested. This ensured that the Society would remain an association of people rather than an aggregation of capital. It prevented a hostile takeover by wealthier members and maintained the egalitarian ethos of the founders.

The Dividend on Purchase (The “Divi”)

The economic genius of the Rochdale system was the “dividend on purchase.” Previous cooperative attempts had often sold goods at cost price, which left them with no margin for error or capital accumulation and antagonized local shopkeepers who launched price wars. The Rochdale Pioneers, however, decided to sell goods at prevailing market prices. The surplus generated (after expenses and reserves) was then returned to members in proportion to their expenditure at the store, not their capital investment.

This mechanism accomplished three critical functions: it created Loyalty by giving members a financial incentive to shop at the store; it drove Capital Formation by retaining surplus until the quarter’s end; and it ensured Conflict Avoidance by not undercutting local private traders.

Capital as a Servant

The 1844 rules stipulated that capital invested in the Society (shares) would receive a fixed rate of interest (initially 3.5%, later raised to 5%). This was a profound ideological statement: capital was viewed as a hired tool entitled to a wage (interest), but not to the profits of the enterprise. The surplus belonged to the user (the consumer), not the investor.

Cash Trading and Neutrality

Rule 21 and others regarding financial management strictly prohibited the extension of credit. The “strap book” (credit ledger) was identified as a primary cause of working-class indebtedness and the failure of previous co-ops. By insisting on cash trading, the Pioneers ensured the Society’s liquidity and protected members from the moral and financial hazard of debt. Furthermore, although the Pioneers themselves were men of strong conviction - Chartists, Socialists, Unitarians - the rules established a platform of political and religious neutrality, allowing the Co-op to serve the entire working class.

The Founders: A Sociological Profile

The mythology of the “Twenty-Eight Weavers” often obscures the occupational diversity and political sophistication of the founders. They were not a random assortment of the poor, but a coalition of the “labor aristocracy” and the politically active. Historical records reveal a diverse group:

- Charles Howarth (Warper): The Architect who drafted the rules and devised the dividend system.

- James Smithies (Wool Sorter): Known as the “laughing philosopher,” he served as Secretary and Director, organizing the education department.

- William Cooper (Weaver): The Administrator and first Cashier, who dedicated his life to the Society’s correspondence.

- James Daly (Joiner): The Builder and first Secretary, who built the shop’s fixtures from recycled timber.

- Samuel Ashworth (Weaver): The Salesman who stood behind the counter on opening night.

- Miles Ashworth (Flannel Weaver): The first President, who had previously served as a guard to Robert Owen at the Queenwood community.

- James Standring (Weaver): The Activist involved in the Ten Hours movement, who weighed the flour on opening night.

- Samuel Tweedale (Weaver): The Orator, known as the “talking man” of the store.

- James Tweedale (Clogger): A director representing the cloggers, a distinct trade from the weavers.

- John Bent (Tailor): A socialist Auditor who ensured the financial integrity of the early books.

They were united not by a single trade, but by a shared ideology and a shared necessity.

The Shop: 31 Toad Lane as a Socio-Economic Laboratory

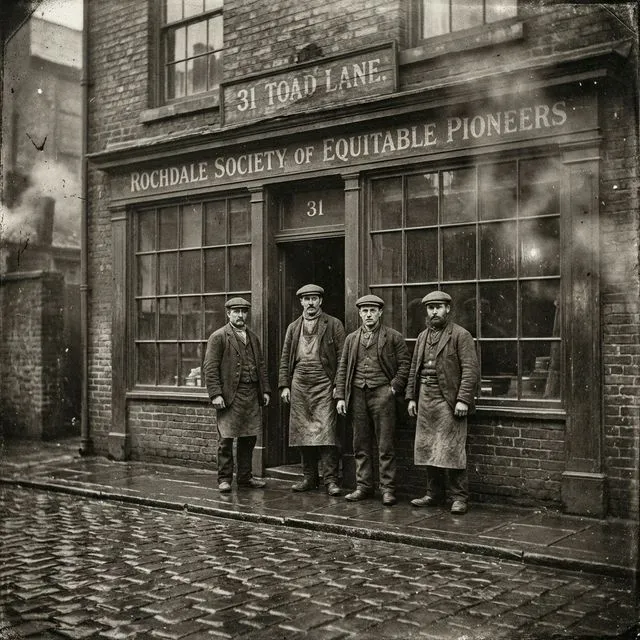

The physical establishment of the store was a harrowing ordeal. The Society rented the ground floor of a warehouse at 31 Toad Lane for £10 per annum. The location was symbolic; the upper floors were occupied by a Bethel Chapel, placing the cooperative physically between commerce and non-conformist religion.

On the evening of the Winter Solstice, December 21, 1844, the store opened its doors. The atmosphere was tense. Outside, “doffer boys” (factory lads) and skeptics gathered to jeer, making jokes about the “weavers’ dream” and the wheelbarrow that was rumored to contain their entire inventory. The gas company had refused to supply the building, fearing the Society would collapse before paying the bill, so the shop was lit by tallow candles.

James Smithies took down the shutters. William Cooper sat at the desk as cashier, and Samuel Ashworth stood behind the counter. The shop opened for business at 8:00 PM. The initial capital raised was £28. After fitting out the shop (using planks on barrels as a counter), they had approximately £16 left for stock. The inventory was stark:

- Butter: 28 lbs

- Sugar: 56 lbs

- Flour: 6 sacks

- Oatmeal: 1 sack

- Candles: A small quantity.

Despite the meager selection, the Pioneers offered something revolutionary: Purity. In the 1840s, food adulteration was rampant. Flour was commonly mixed with chalk, alum, or plaster of Paris to increase weight and whiteness. Sugar was mixed with sand; tea with iron filings; coffee with chicory. The Pioneers pledged to sell “pure food” at “honest weight.” They refused to engage in the deceptive retail practices of the time, such as using “short weights” or loss leaders to trap customers. This commitment to quality became their primary marketing tool.

Social Change: The Republic of Consumers

The impact of the Rochdale Pioneers extended far beyond the balance sheet. Fulfilling the “Law and Objects,” the success of the store provided the material base for a profound social transformation in Northern England.

The dividend system functioned as a socio-economic liberator. In 19th-century industrial families, women were the primary managers of household consumption but rarely controlled capital. The “divi,” paid out quarterly in a lump sum, provided women with a mechanism to accumulate significant savings “without trouble to themselves.” This accumulated capital was often used for “lumpy” expenditures that were otherwise out of reach, such as new clothes for Whitsuntide, school fees, or medical emergencies. In many instances, the Co-op divi saved families from the workhouse during periods of unemployment.

Furthermore, the Pioneers understood that a cooperative commonwealth required cooperative citizens. In 1854, they formalized their commitment to education, allocating 2.5% of all trading profits to an education department. This was a radical act in an era when the state provided negligible education for the working class. The Society utilized the upper floors of the Toad Lane warehouse to establish a newsroom and a library. By the 1860s, the library contained thousands of volumes and the newsroom subscribed to leading daily papers, quarterlies, and radical journals. They even purchased scientific instruments, such as globes and microscopes, for members’ use. The education department organized lectures on everything from chemistry to political economy, creating a “University of the Working Class.”

By 1867, they had also fulfilled the second objective of their rules by entering the housing market, constructing a “Co-operative Town” - a series of cottages for members noted for their superior sanitation. They created a parallel civil society, a “Republic of the Streets,” with its own governance and welfare systems, where men and women learned to audit accounts, speak in public, and manage large enterprises.

Global Reach: The Rochdale Diaspora

The “Rochdale Model” proved to be exceptionally portable. Unlike the complex and often authoritarian structures of Owenite communities, the Rochdale rules were simple, scalable, and adaptable.

The success of Toad Lane inspired a wave of imitation across the industrial North. By 1851, there were over 130 retail co-operative societies in the North of England and Scotland. To support this network, the Rochdale Pioneers spearheaded the formation of a federal body. In 1863, the North of England Co-operative Wholesale Industrial and Provident Society (later the Co-operative Wholesale Society or CWS) was founded in Manchester. This federation allowed local societies to pool their purchasing power to buy directly from importers and manufacturers. The CWS eventually grew into a colossal manufacturing and shipping empire, owning tea plantations, steamships, and factories.

The principles traveled internationally through correspondence and emigration. In North America, the first Rochdale-model store opened in Stellarton, Nova Scotia, in 1861. In the United States, the Union Cooperative Association No. 1 of Philadelphia (1862) adopted the Rochdale bylaws, and the Granger movement in the 1870s embedded these principles into the American rural economy. While European movements like the German credit unions (Raiffeisen) developed differently, the consumer-focused Rochdale model became the gold standard for consumer cooperation.

The globalization of the movement culminated in 1895 with the founding of the International Co-operative Alliance (ICA) in London. In 1937, and subsequently in 1966 and 1995, the ICA formally codified the “Rochdale Principles” as the universal standard for cooperatives worldwide, ensuring that the DNA of the 1844 rules - democratic control, member economic participation, and concern for community - remained intact.

Conclusion

The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers represents one of the most successful social experiments in history. From a damp warehouse in a Lancashire mill town, a group of artisans devised a mechanism that could harness the power of consumption for the collective good.

Their legacy is threefold. First, legally, they proved that a voluntary association of working people could operate a complex business within the framework of the law, protecting their assets and ensuring democratic control. Second, economically, they demonstrated that the “dividend on purchase” could break the cycle of debt and allow the poor to accumulate capital. Third, socially, they showed that commerce could be a school for citizenship, creating a “state within a state” where education, housing, and welfare were guaranteed not by the government, but by the mutual self-help of the community.

The “Law and Objects” of 1844 remains a seminal text. It reminds us that the Pioneers were not content with merely selling cheaper flour; they aimed for a “self-supporting home-colony.” While the utopian colony was never fully built, the global cooperative movement - numbering over a billion members today - stands as the enduring edifice of their vision. The light lit at 31 Toad Lane in 1844 has never truly gone out; it has merely been refracted through millions of other storefronts across the world.

References & Further Reading

- The History of the Rochdale Pioneers (1844-1892) by George Jacob Holyoake

- The Rochdale Pioneers and the Co-operative Principles by Columbia University

- Rochdale Pioneers Rules 1844 (Original Historical Text)

- Guidance Notes to the Co-operative Principles by International Cooperative Alliance

- The Hungry Forties: Crisis and Reform (UEA Research Repository)