The Birtley Belgians: A Sovereign Enclave in County Durham

Introduction: An Anomaly of War

In the vast and tragic history of the First World War, few stories are as peculiar or as significant as that of the “Birtley Belgians.” While the conflict is usually remembered for the static horror of the trenches or the grand geopolitical maneuvers of the Great Powers, a unique experiment in transnational cooperation was unfolding in the industrial heartland of Northern England. Here, in Birtley, County Durham, a piece of foreign territory was effectively carved out of the British landscape.

This was not merely a refugee camp or a temporary shelter. It was a sovereign enclave, a “state within a state” known as Elisabethville. Within its guarded perimeter, British law was largely suspended, the currency was different, and the police force wore the uniforms of a foreign nation. Born from the desperate industrial necessities of 1915, this colony of wounded soldiers - the invalides - and their families became a crucial component of the Allied war machine, manufacturing the heavy artillery shells that were desperately needed to break the deadlock on the Western Front.

1. The Context: A Geopolitical and Industrial Crisis

The Collapse of the Old Order

To understand the genesis of the Elisabethville colony, one must first appreciate the catastrophic strategic failures that defined the opening year of the Great War. By the spring of 1915, the illusions of a rapid war of movement - anticipated by military planners in London, Paris, and Berlin - had been shattered. The conflict had calcified into a gruesome stalemate.

The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), proudly styling themselves the “Old Contemptibles” after a disparaging remark by Kaiser Wilhelm II, had performed with remarkable resilience during the initial retreat from Mons and the First Battle of Ypres. However, their pre-war training was ill-suited for the reality they now faced. They were trained for rapid musketry and maneuver warfare, tactics that were rendered obsolete by the industrial attrition of the trenches.

The Shell Scandal of 1915

The deadlock was exacerbated by a profound failure in industrial mobilization known as the “Shell Crisis.” Until 1915, the British War Office had operated on the fatal assumption that traditional suppliers - great armament firms like Vickers and Armstrong Whitworth - could simply surge their existing capacity to meet wartime demand. This calculation proved drastically wrong.

The expenditure of ammunition in the first months of the war exceeded all pre-war estimates by orders of magnitude. For instance, at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915, British artillery units expended more shells in a single thirty-five-minute bombardment than heavily engaged units had fired during the entire duration of the Boer War. Tragically, this immense expenditure yielded negligible strategic gains. The primary reason was the type of munition available. The British arsenal was heavily weighted toward shrapnel shells, which were effective against troops moving in the open but useless against men dug into the earth. The army critically lacked High Explosive (HE) shells, which were required to pulverize barbed wire and destroy hardened trench fortifications.

This industrial failure spilled into the public arena through a concerted press campaign, led most notably by Lord Northcliffe’s The Times. The newspaper published scandalous revelations that British soldiers were dying needlessly due to a lack of ammunition. The resulting political firestorm brought down H.H. Asquith’s Liberal government and led to the formation of a coalition. Crucially, it resulted in the creation of the Ministry of Munitions under David Lloyd George. This new ministry was granted unprecedented powers to intervene in the economy, effectively nationalizing the war effort. The solution they proposed was the rapid construction of “National Projectile Factories” (NPFs) - state-owned facilities managed by private expertise but dedicated solely to the mass production of heavy-caliber ammunition.

The Belgian Exodus and Labor Shortages

While Britain grappled with an industrial crisis, Belgium faced an existential catastrophe. The German invasion of August 1914 had shattered the Belgian army and displaced a vast segment of the civilian population. The advancing German troops committed a series of war crimes known as the “Rape of Belgium,” which precipitated a massive refugee crisis. Approximately 250,000 Belgians fled across the English Channel to Britain, seeking sanctuary from the occupation.

This influx presented the British government with both a challenge and an opportunity. The domestic workforce had been decimated by voluntary enlistment, leaving essential engineering and munitions industries with a severe shortage of skilled labor. The proposed “dilution” of labor - bringing women and unskilled workers into factories - was fiercely resisted by British trade unions. Into this vacuum stepped the Belgian refugees. Belgium had long been one of Europe’s premier industrial nations, possessing a workforce highly skilled in metallurgy, engineering, and armaments manufacture.

However, integrating these workers was complex. Issues regarding language barriers, differing industrial practices, and trade union sensitivities about foreign labor “undercutting” British wages made direct integration difficult. The solution arrived at was radical: rather than dispersing Belgian workers into British factories, the government would create a dedicated, segregated Belgian industrial enclave.

2. The Anglo-Belgian Convention: A Legal Anomaly

The legal and diplomatic framework for this experiment was established through the Anglo-Belgian Convention, signed on February 11, 1916. This agreement was a remarkable instrument of transnational cooperation. It stipulated that the British Ministry of Munitions would finance the construction and operation of a National Projectile Factory at Birtley. In return, the Belgian government-in-exile, operating from Le Havre, would provide the management and the workforce.

The agreement was unique in that it granted the Belgian management a degree of autonomy that bordered on total sovereignty. The factory was not merely to be staffed by Belgians; it was to be run according to Belgian industrial customs, under Belgian military law, and managed by a Belgian directorate. This effectively created a sovereign enclave of the Kingdom of Belgium transplanted into the coalfields of County Durham.

The site chosen was strategic. Birtley, located between Newcastle and Durham, possessed the necessary rail links via the North Eastern Railway. It was also situated near existing industrial works, specifically the Armstrong Whitworth plant, which would initially oversee the project before handing over full control to the Belgians.

3. Elisabethville: Anatomy of a Sovereign Village

Architecture and Infrastructure

To house the workforce required for the National Projectile Factory, a purpose-built village was constructed adjacent to the industrial site. It was named Elisabethville in honor of Queen Elisabeth of Belgium. Far from being a temporary camp, this was a fully functioning town designed to accommodate up to 6,000 people, comprising workers, their wives, and their children.

The architectural landscape of Elisabethville was defined by “hutments” - prefabricated wooden structures that served as the primary accommodation. These were rigorously categorized based on the demographic profile of the residents:

- Barracks: Large, dormitory-style blocks designated for single men or unaccompanied workers. These were functional and spartan, reflecting the military discipline under which the single men lived.

- Cottages: Smaller, self-contained units for families. These came in two sizes and were fully furnished by the government.

- Hostels: Specialized accommodation for the administrative and supervisory staff.

The layout of the village mimicked the “garden city” ideal, featuring wide avenues and clearly demarcated public spaces. The street names reflected the geopolitical alliance, with the main thoroughfare named Elisabeth Avenue, and others named Rue de Kitchener and Rue de Lloyd George.

Social Tension and Housing Conditions

A point of significant local tension was the quality of these “temporary” homes. In the early 20th century, housing conditions for the British working class in County Durham were often poor, characterized by overcrowding and a lack of sanitation. By contrast, the huts of Elisabethville were equipped with electric lighting, internal flush toilets, and running water - amenities that were considered luxuries by the local population in Birtley.

This disparity generated a complex dynamic. While the locals sympathized with the “poor refugees” in the abstract, the tangible reality of the refugees living in superior accommodation, funded by the British taxpayer, was a source of friction. The enclave was physically separated from Birtley by a high iron fence and guarded gates, which further emphasized the separation between the two communities.

Institutions of Autonomy

Because of its isolation, Elisabethville was designed to be autarkic. The enclave possessed a full suite of internal institutions:

- Education: A primary school was established to educate the 1,200 children living in the colony. The curriculum was strictly Belgian, taught in French and Flemish, ensuring that the children could be reintegrated into the Belgian education system upon repatriation. The school building was of such high quality that, although intended to last only ten years, it remained in use for nearly sixty years after the war.

- Religion: Spiritual life was central to the predominantly Roman Catholic community. St. Michael’s Church was built within the colony and staffed by Belgian clergy, providing a spiritual anchor for the exiles.

- Commerce: The village had its own butcher, grocer, and general stores. These were functioning shops rather than mere ration distribution points. A large dining hall, the “Cheval Blanc” (White Horse), served as a communal eating place and social hub.

- Healthcare: A dedicated hospital with 100 beds was staffed by Belgian doctors and nurses. It treated industrial injuries from the factory as well as the general ailments of the civilian population.

- Postal Independence: A sovereign British Sub-Post Office operated within the village. While it sold British stamps, it was staffed by Belgian postal workers, further blurring the lines of sovereignty.

4. The “Birtley Bark” Economy

One of the most distinctive features of the colony’s independence was its internal economy. To control the flow of currency and limit economic interaction with the surrounding British town (and the associated vices of gambling and drinking), Elisabethville utilized a proprietary token system.

Often referred to in local lore as “Birtley Bark” (a term that may have also referred to the newspaper), these were officially canteen tokens produced by the Newcastle firm Van Der Velde. The tokens were minted in brass and zinc alloy and functioned as a de facto currency within the enclave.

They were issued in the following denominations:

- 1 Shilling (1/-): Brass, featuring the legend “AU CHEVAL BLANC / ELISABETHVILLE”.

- 6 Pence (6d): Brass.

- 4 Pence (4d): Zinc Alloy, featuring a map of Great Britain on the reverse.

- 3 Pence (3d): Zinc Alloy.

- 1 Penny (1d): Zinc Alloy.

This token system served a dual purpose. Economically, it kept the wages paid to the workers circulating within the colony’s own commercial ecosystem. Socially, it acted as a barrier to interaction with Birtley, as the tokens were zero value outside the gates of Elisabethville.

5. Governance, Discipline, and the 1916 Riot

The Invalides and Military Law

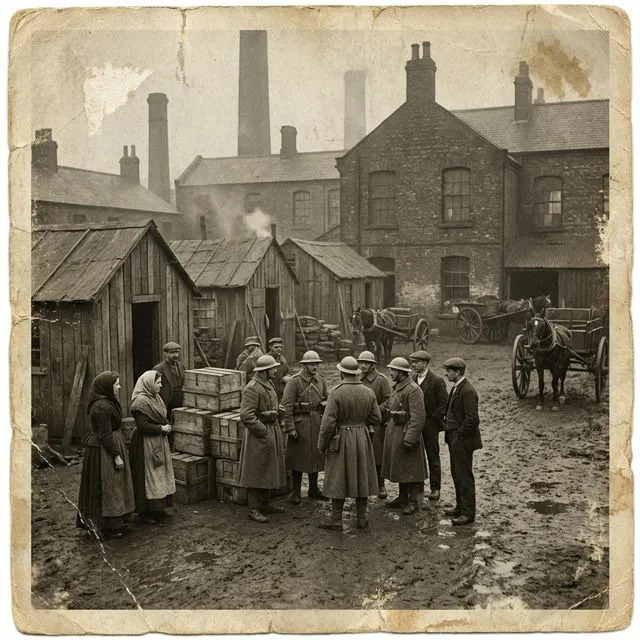

The governance of Elisabethville was a strictly military affair. The residents were not merely refugees; the majority of the male workforce were invalides - soldiers who had been wounded in the early campaigns of the war and withdrawn from the front. Although physically unfit for trench warfare, they were still considered active members of the Belgian Army and were subject to military discipline.

This legal status created a unique policing situation. The colony was patrolled by the Belgian Gendarmerie, the paramilitary police force of Belgium. However, their jurisdiction in Birtley was fraught with legal ambiguity. While they enforced Belgian military law within the fence, they were theoretically operating under British civil law. A major point of contention was the carrying of sidearms. In Belgium, Gendarmes were routinely armed with pistols; in Birtley, British authorities, wary of armed foreign troops on domestic soil, prohibited the Gendarmerie from carrying weapons except under “special circumstances” approved by the local British Chief Constable.

The Explosion of Tensions

The imposition of strict military discipline on a workforce engaged in arduous industrial labor created a pressure cooker environment. Belgian workers were required to wear their heavy wool military uniforms at all times, even when working near the intense heat of the shell furnaces. They were also required to salute officers and adhere to curfews. This friction was exacerbated by the linguistic and class divide within the Belgian contingent: the management and officer class were largely French-speaking Walloons, while the workforce was predominantly Dutch-speaking Flemish.

These tensions exploded on December 20, 1916. The catalyst was a seemingly minor infraction: a worker was imprisoned by Captain Algrain, the Military Head of Security, for wearing a civilian cap with his military uniform while requesting leave. This arrest, perceived as an act of petty tyranny, sparked a mass uprising. A crowd of approximately 2,000 workers marched on the Gendarmerie station, tearing down fences and smashing windows with stones. The riot was of such scale that the unarmed Gendarmes were overwhelmed. Order was only restored through the intervention of the local British police and senior management, who mediated with the rioters.

The aftermath of the riot led to significant reforms. A commission of inquiry resulted in the removal of Captain Algrain, who was replaced by Captain Commandant Noterman. Crucially, the requirement to wear military uniforms in the factory and village was relaxed, marking a shift from a purely penal-military atmosphere to a more civilianized industrial regiment.

6. Cultural Identity and The Birtley Echo

To maintain morale and foster a sense of community, the colony produced its own newspaper, the Birtley Echo. Published weekly starting in 1917, the paper was a trilingual publication (French, Flemish, and English), reflecting the linguistic diversity of the enclave.

The Echo served multiple functions. It was a gazette for official announcements from the Belgian government in Le Havre and the factory management. It was a news source, providing updates on the progress of the war. But perhaps most importantly, it was a cultural outlet. The paper featured cartoons, sketches, and satirical articles that commented on the strangeness of their exile. One notable cartoon, “Croquis et Silhouettes: Le ‘Plaisir’ d’aller a Newcastle” (November 24, 1917), humorously depicted the “pleasure” of a trip to Newcastle, highlighting the culture shock experienced by the refugees.

The cultural life of the village extended beyond the newspaper. The Belgians established a symphony orchestra with over 40 members, a brass band, and several dramatic societies. These groups utilized Birtley Hall for performances, often raising funds for Belgian relief charities. Sporting clubs flourished, including football teams and a swimming club that used the River Wear. This vibrant associative life was a way for the refugees to reclaim agency and dignity in a situation where they had lost their homes and, to some extent, their freedom.

7. The National Projectile Factory No. 1

Management and Workforce

The National Projectile Factory (NPF) at Birtley was unique in the British war industry. While built by the British firm Armstrong Whitworth, operational control was handed over entirely to the Belgian government. The factory was led by Director-General Hubert Debauche, a formidable industrialist who had managed large iron and steel works in Gilly, Belgium, before the war. Debauche’s management style was paternalistic but rigorous, mirroring the structures of Belgian heavy industry.

The workforce initially consisted of about 1,000 skilled workers, but this quickly grew. By 1918, the factory employed approximately 3,980 men. Unlike other British munitions factories, which relied heavily on female labor (“munitionettes”), the Birtley NPF was an almost exclusively male environment, owing to its military character. Only about 288 women were employed, and they were restricted to clerical and administrative roles.

Production Processes

The factory was dedicated to the production of heavy-caliber ammunition. The production process was documented in a series of high-quality photographs taken in June 1916 (Tyne & Wear Archives). These images provide a forensic record of the factory floor:

- Forging: Giant hydraulic presses shaped red-hot steel billets into the hollow bodies of shells. The heat in these shops would have been intense, making the initial requirement for wool uniforms particularly onerous.

- Machining: Rows of lathes, operated by Belgian soldiers, turned the rough forgings into precision-engineered projectiles. Workers were tasked with “filing weight off the radius” and cleaning the exterior casings.

- Assembly: Critical stages such as “pressing the copper band” (the driving band that engages the gun’s rifling) and “riveting the base plate” were performed with exacting precision.

- The Bond Store: The final stage involved the Bond Store, a cavernous warehouse stacked floor-to-ceiling with thousands of completed shells, ready for inspection and dispatch to the front.

Output and Efficiency

Despite the physical limitations of the workforce - many of whom were missing limbs or suffering from other war wounds - the Birtley NPF achieved extraordinary levels of productivity. It was widely reported that the Birtley factory had the highest output per capita of any projectile factory in the United Kingdom.

By the end of the war, the factory had produced over 2 million shells. The specific breakdown of their contribution is as follows:

- 6-inch High Explosive & Chemical: 993,900 shells.

- 60-pounder Shrapnel: 589,500 shells.

- 9.2-inch Shells: 448,000 shells.

- 8-inch Shells: 9,600 shells.

The total output exceeded 2,050,000 shells. These munitions, manufactured by wounded Belgian exiles in Durham, were fired by British gunners at the Somme, Passchendaele, and during the Hundred Days Offensive that finally broke the German army.

8. Post-War: Repatriation and Legacy

The Logistics of Return

The Armistice of November 11, 1918, brought an abrupt end to the Elisabethville experiment. With the cessation of hostilities, the strategic necessity for the factory vanished, and the political imperative shifted to repatriation. The British government, facing its own demobilization challenges and rising unemployment, was eager to reclaim the site.

The repatriation process began almost immediately. On November 11, 1918, the very day of the Armistice, plans were activated. The factory ceased production of shells, briefly switching to aircraft bombs in 1919 before closing entirely. The repatriation was organized by the Belgian Repatriation Committee, which prioritized the return of skilled workers needed to rebuild Belgium’s shattered infrastructure.

Special trains transported the refugees from Birtley to the ports of Newcastle and Hull. From there, ships carried them back to Antwerp and Ostend. The first large groups left in January 1919. Records show specific families departing, such as Theresia Peeters and her six children, who returned to Aarschot on January 21, 1919. By February 1919, the village of Elisabethville was largely deserted.

The Great Sale and Demolition

The departure of 6,000 people left behind a ghost town filled with furniture and household goods. In May 1919, the British government organized a massive auction to liquidate the colony’s assets. The Daily Mail described it as “the largest furniture sale on record.” Thousands of items - beds, wardrobes, tables, chairs, and crockery - were sold off to local dealers and residents. For decades afterwards, it was common to find “Elisabethville furniture” in the homes of Birtley and Gateshead.

The physical structures of the village faced a bleaker fate. While some of the huts were initially rented out to local families to alleviate the post-war housing shortage, they were temporary structures not designed for long-term use. By the 1930s, most of Elisabethville had been demolished to make way for permanent council housing.

Memorialization

Today, the physical footprint of Elisabethville has been almost entirely erased. The factory site was eventually taken over by Royal Ordnance and later BAE Systems, continuing a military-industrial legacy until recent years. Of the village, only two original brick buildings - the former butcher’s shop and food store - survived into the 21st century.

However, the memory of the “Birtley Belgians” is preserved. The Elisabethville Roman Catholic Cemetery remains the most poignant site of memory. It contains the graves of thirteen Belgian soldiers and several civilians who died during their exile. For many years, these graves were neglected, but recent restoration efforts have installed new headstones honoring those who “Died for Belgium” (Mort Pour La Belgique).

The story of the Birtley Belgians is a powerful counter-narrative to the standard history of the British Home Front. It reveals a moment when the pressures of total war forced the British state to cede sovereignty over a patch of its own territory, allowing a community of foreign exiles to build a thriving, independent society in the heart of the industrial North.

References & Further Reading

- The Birtley Belgians: WWI Refugees in the North (Contextual Source)

- Belgian Refugees in Britain (The Low Countries)

- The British Home Front and the First World War (Cambridge University Press)

- Belgian Exiles, the British and the Great War (ResearchGate)

- National Projectile Factory Birtley (British War Work Tokens)